“LET’S GO TO THE CANDY STORE!”

I don’t know who said it first. Any one of us three kids, maybe. My family was on vacation up north, in a cottage. It could have been a subliminal suggestion implanted by a neighbor who was sick to death of us behaving like children (gasp!) while he sat on his front porch being old. And by “subliminal” I mean “yelling.”

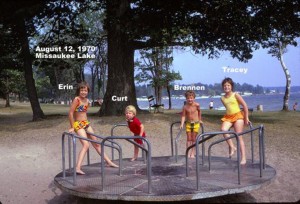

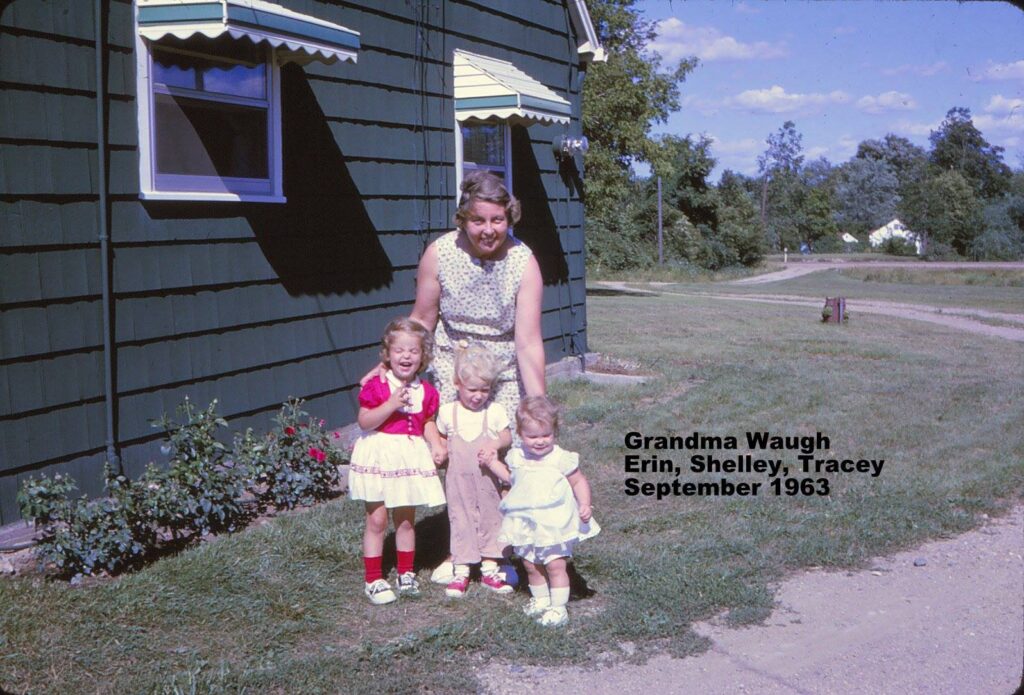

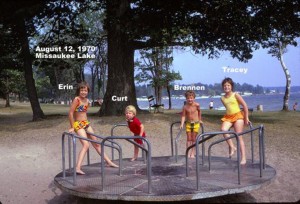

There were actually four kids in all. I was 10, my sister Tracey (8), my brother Brennen (5), and my brother Curt (3). I was the oldest; I have always been the oldest (!) so I could never escape that quirky little birthright of being “in charge.” As you will see, the limits of my shepherding skills maxed out at “Maybe candy will stop him from dying like that.”

Only three of us will take the pilgrimage to the candy store. (Curt was too “baby.”) Three kids will leave on this journey; one will be carried home. This is a story about thirst. It is a story about Lik•m•aid. It is a story about the miracle that any child manages to survive to the age of reproduction. I bet Darwin liked candy.

We were regular folk. My family was as ordinary as a Pez dispenser. Mom, dad, four kids. My father was an engineer at Chevy; my mother was the engineer of our household. My father designed systems that made a car go; my mother packed automobiles with cargo. (I’m sorry. It’s my upbringing. Plus I’m full of Smarties.)

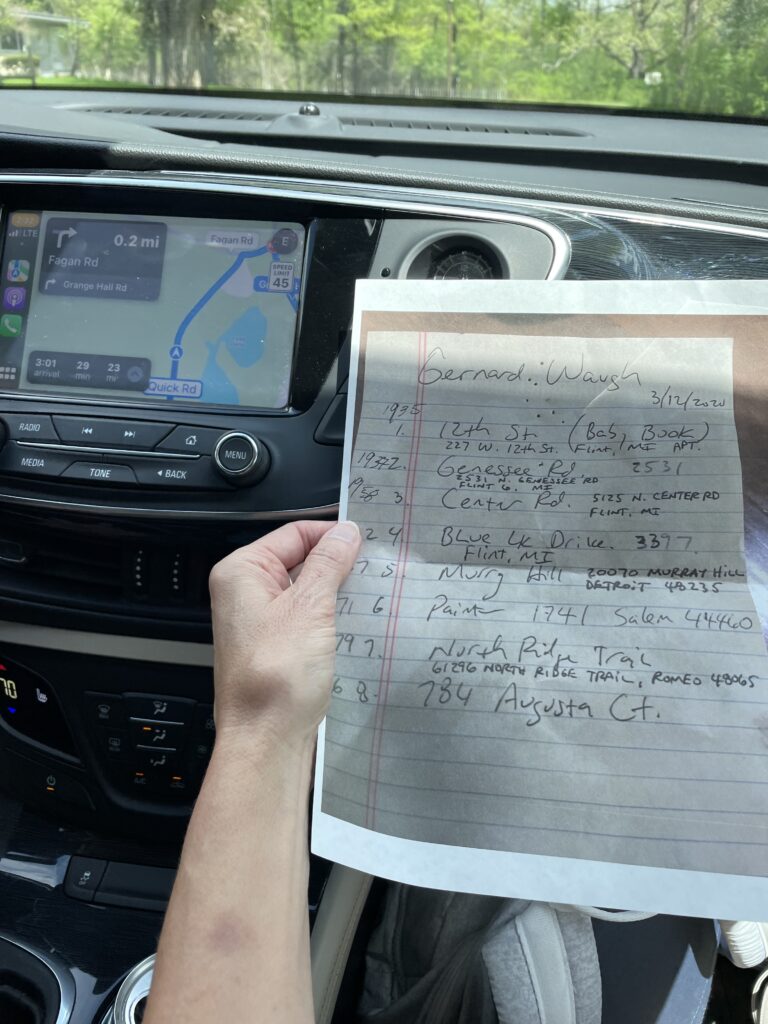

It was the late 1960s. We lived in Detroit just south of Eight Mile Road. We were area code 3-1-3 before it was rap-worthy. My father had been transferred from Flint, Michigan, (where we all were born) to Detroit, Michigan, (where one of us nearly dies). It was practically the law that families had to live in a red brick ranch on a paved street. Perspective is a convenient trick of childhood. The house was tiny, but it felt enormous, roomy enough to sponsor the chaos. We ate Wonder Bread and threw Jarts. We drank Kool-Aid and crashed bikes into trees. We walked to public school, lost our shit when the ice cream man jingled by, and tripped our brothers when nobody was looking. There was a park down the street. It was the law.

The houses were all alike, but the people were a kaleidoscope — diverse bins of color and flavor. My “boyfriend” was Latino. Curt went to a Jewish nursery school. Tracey and I swam in our black friends’ backyard pool. Our neighbors were smokers and athletes. Our neighbors were teetotalers and wine-makers. Our neighbors were Sabbath-keepers who made kosher sausage in their kitchens. They were Catholics in plaid and Protestants in orange. There was a “special” young man who frequently escaped his house, naked, screaming that his mother was trying to beat him with a belt. She wasn’t. Or maybe she was.

One time my brother Brennen asked if his new friend Valentine could come over and play.

“Of course,” answered my mother. (Everybody came to our house. We have always had what I call a “Kool-Aid House.” You pour it, they will come.) “But are you sure that’s his name? Valentine?” My mother was both reasonable and open to absurdity.

Brennen, with the appalled confidence of a four-year-old: “Yes. His name is Valentine.”

When “Valentine” finally came over to race Hot Wheels and eat graham crackers, my mother asked him his name.

“Cervantes,” said the kid.

“Okay,” my mom nodded. “You can call him ‘Valentine.’” The kid agreed, then ate a Popsicle.

—————————————–

And now we were on vacation. If you lived in Michigan in the 1960s and your dad worked for one of the automakers, it was also some kind of law that you went “up north” for vacation. People packed enormous suitcases into enormous cars and drove north to experience even more colors, more flavors, and more deprivation. “Let’s drive someplace where everything is just harder to accomplish.” That seemed to be the main purpose of going up north. The ride took 3 to 20 hours depending on how long your toddler could “hold it.” Kids fought over the “way back” in the station wagon so they could be further from mother-hands. In a regular sedan, we laid Curt up in the rear window. He hardly ever burned to death.

“Up north” for us meant “The Cottage.” The Cottage was a long, low ranch house in northern Michigan owned by my grandparents. The Cottage was unoccupied all year except during the summer. (SUMMER!! As a kid, summer in was all caps. Rare and magical as a LEPRECHAUN!!)

In the spring, The Cottage had to be o-p-e-n-e-d. The Opening of The Cottage was a mysterious and complex ceremony involving wrenches and wizardry. Every June my grandmother would welcome us to The Cottage with wild hair and a lavish hug even as she dismissed the box of (apparently) torture implements in the corner. “Well,” she would mutter, glancing at the hammer and the bible, “we had to open the house.” This was sometimes followed by a shot of scotch and a “Mother Mary full of grace,” or whatever German Lutherans whispered. My grandmother was a good German Lutheran who believed in the power of smiling and sorcery, which she practiced in equal measure alongside prayer and hard work. And cooking enormous pots of cabbage. And chicken. And lots and lots of love. I never actually witnessed “the opening of the house.” I assume it included sauerkraut.

The cottage had three bedrooms, a fireplace for heating, and a rabbit-eared TV that only played the news. Occasionally the weather. (“Shhh…! The weather!”) The kitchen was so small that only one adult or two children could fit in there at any one time. My sister and I banged up our shins and elbows just to wash dishes. (Okay, that’s what we told our parents. Mostly Tracey just beat me up.) I’m kidding! (She made me say that.)

Across the street was Cedar Lake where we swam, waterskied, and held our breath under water. For encouragement, we pushed each other down by the throat. (Tracey won these contests, Brennen giggled, and Curt stood ankle-deep on the shore and cried.) There was a dock for cannonballing and a fishing boat for swearing. With hot water at a premium, we frequently bathed right there in the lake with a bottle of Prell. This was before pollution, before flesh-eating bacteria.

“Rinse your brother off.”

“Why me?”

“Because you’re in charge.”

Curt was often sudsy.

The Cottage was in Oscoda, Michigan, near the Au Sable River. “Oscoda” is a Native American word meaning “mosquito bite,” and “Au Sable” is French for “bleeding to death.” There were so many mosquitoes at The Cottage that by summer’s end you could barely hold your head up from the anemia. (“Walk it off!”) And yet eight of us (four adults and four children) somehow managed to sleep, eat, and play for weeks at a time without resorting to savagery. It was glorious. There was a rope for swinging and a hatchet for chopping, neither of which was ever turned into a weapon.

And there was a candy store.

———————————————-

Kids get bored, even during the summer. (SUMMER!). With so many formless hours to fill, even civilized children will turn to petty torment if not diverted.

(HAHAHA!! “Civilized children.” You thought finding a leprechaun was rare? Children will make him medium rare.)

Back to our story…

“Let’s go to the candy store!”

I still don’t know who said it first. It might even have come from one of the grown-ups.

“How ‘bout you sonsabitches go to the candy store?”

Nah, they didn’t talk like that. More like:

“Shhh…! the weather!”

Or maybe it was Curt. He was only 3, but he needed a break from our contests. Guantanamo has nothing on the creativity of a big sister.

Here’s what I remember: I was 10, Tracey was 8, and Brennen was 5. And Brennen was alittle 5. Goofy, trusting, happy as a golden retriever. And little. The candy store was actually a gas station down the street and around the corner from The Cottage. That way. Sort of. I knew this only as a vague distant fact.

Here’s what I remember: somehow the three of us kids found quarters our hands and time to kill. Somehow we were walking. To the candy store. Alone.

It was a blistering summer day. We walked down the gravel road past a long line of cottages. Every cottage was different, but the same. Every cottage hid under the camouflage of a stack of cordwood, an ancient tree, and a proud but tired sign. “The Jones Family.” “Ed and Tina Farnsworth.” “The Hathaways!” The dust from the road made us cough. We kept walking. I was in charge.

We turned to the right when the two roads met. I was 50% sure this was correct. We kept walking. The sun baked our heads, no hats, no sunscreen. This was the 60s, before cancer. The coins in our hands grew damp and heavy.

I asked my sister how much further she thought it was. Tracey rammed her elbow into my ribs and rolled her eyes. “I don’t know. You’re in charge!”

Brennen, behind us, picked up a stick, smiled. He took a swing at an overhead tree, smiled. He could barely reach. WHAM! Mosquitoes devoured us. Smile.

“Are we there yet?” Tracey wrapped her knuckles around the weight of her quarters and punched me in the arm. I sneezed out dirt.

Finally, up ahead, an oasis. THE CANDY STORE!

“Come on, you guys!”

We run, the coins like magic beans that we will trade for candy. Three cars are parked in the lot and two are filling up at the gas pumps. We run towards the front door like refugees. We burst inside and lose our minds.

Dots! Milk Duds! Lik•m•aid!

We pluck, dicker, change our minds. We negotiate a trade agreement: three of your Swedish Fish for six of my Sugar Babies. DEAL! We pay the man, head out with our treasures. The sweets spill from our pockets, from our bags, from our mouths. I peel a pink Dot off a strip of white paper with my teeth. I hold the door for my brother and sister. We walk into the sunshine. I am delirious.

Brennen says he’s thirsty. He spots a green long-handled pump behind the candy store. Brennen tries to pump the handle, but it’s too big for him. He’s 5. He jumps, but he can’t reach.

I eat another Dot off the paper. Yellow! It’s probably different than pink!

I reach up to help my baby brother, because he’s thirsty, because I’m tall. And I’m in charge. I bite off another Dot. Blue! I pull on the green handle once, twice, three times. Brennen puts his mouth fully over the nozzle and chugs.

It is kerosene.

But I don’t know this. What I know is that time collapses. It is the size of faucet hole. One cartoon gumball bounces slowly across the parking lot, like a moon walk. No gravity. Then something jaw-kicks the universe, and everything tips over. Especially Brennen. He falls forward and throws up.

No, he doesn’t just throw up. He kind of explodes from his mouth. The 10-year-old in me (because that’s all I have) concludes from Brennen’s full-body turbulence that the water tasted bad and he just needs something to mask the flavor.

I hold a pouch of sweet red powder out to him. “You want some Lik•m•aid?”

Brennen throws up again. Hard.

I can’t make sense of what I’m seeing. Brennen’s cheek is on the concrete. I want him to stop doing that. The pavement looks scratchy and hot. And it smells like napalm. Brennen (he’s 5, and getting smaller all the time), is a convulsing puppy.

There was no warning. There was no lock on the pump. There was no “poison” logo. There was no sign that said “Don’t drink this, you dumb shit. It will spoil your vacation.”

A man, a stranger, swoops in and picks Brennen up by his middle, carries him to a giant Buick. Dumps Brennen not gently into the back seat.

“Get in!” The Man yells at us. He points to the passenger side. I climb in the front, Tracey scrambles in beside me.

“Where do you live??” Clenched teeth.

“I don’t know.” Eyes.

And I really don’t know. I have no idea where we live. Detroit? Oscoda? The moon?

I point behind the gas station. “That way?” Not only am I not in charge, I am a terrified kitten. The only reason I don’t wet myself is that it would ruin my candy.

Brennen throws up Starburst and petroleum in The Man’s back seat. The big Buick peels out onto the gravel road. The Man squeals a left turn at the next street, guessing. He slows down, points.

“That one? This one??”

I don’t know. I DON’T KNOW!!

My eyes are everywhere. My tongue finds a small corner of Dot paper stuck to my teeth. I can’t spit it out because my mouth is dust.

A miracle — I spot my grandpa’s car.

“That one!”

The tires throw stones, the big Buick rips into the driveway. The Man runs inside The Cottage, yelling and not even knocking. My mother comes out. Together they pick Brennen up again by his middle. Brennen rewards them by hurling Agent Orange on their shirts.

This story gets worse.

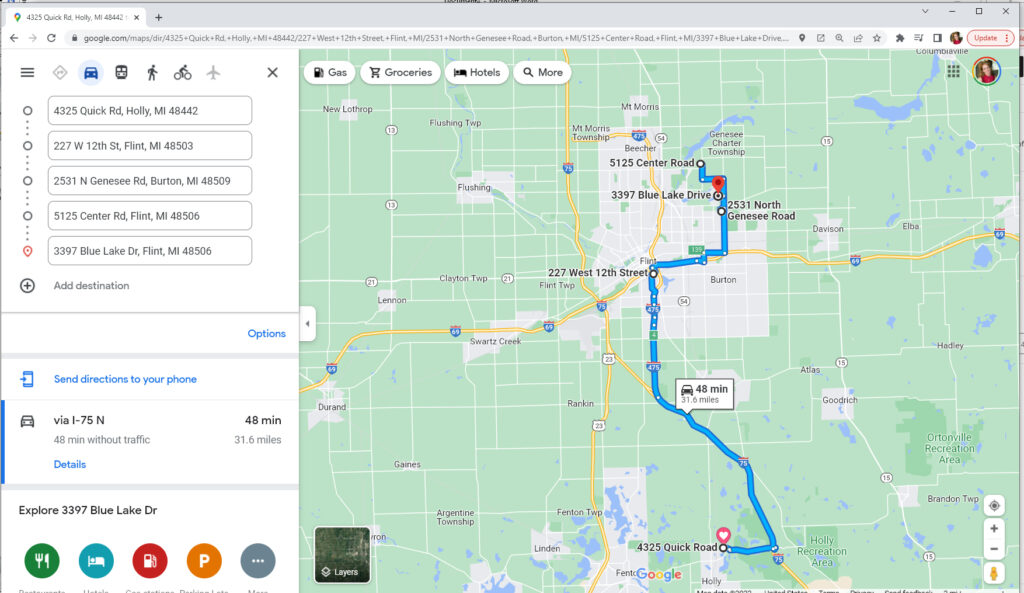

Remember Detroit? Where we also live?

My father had driven back to our real house that morning. He’d had to return for work. When my mother made the panic call to tell him about Brennen’s little mishap, my father answered, “We’ve been robbed.”

Cue time stop. Again.

While we had been up north swimming, getting eaten by mosquitoes, and drinking kerosene, two men had pulled a moving van in front of our real house and carried out the contents. (We only found this out later from neighbors, who hadn’t seen a reason to interfere. The Waughs might have been moving. Who knew? It was the 60s. People were unpredictable.)

Jump start the clock. Again.

My mother piled four children under the age of 10 into my grandfather’s car, and we raced from Oscoda to Detroit. Brennen sat on my mother’s lap in the front seat, eating Saltines and throwing up into a bag. His face was white. He weighed about 7 pounds. The trip took five hours, or maybe a month.

We came home to a scarred brick pretend house. The house looked like it had been beaten up by Joe Frasier, then drank kerosene. The thieves had taken everything of material value. We were unharmed, yes, but we were hurting. The family collectively threw up into a bag.

My brother recovered, mostly because he’s made of Darwinian platinum, not because we did anything right. Brennen grew up to father two children of his own, and as far as I know, neither of them drink kerosene.

I don’t know what happened to The Man except for the many prayers we sent his way.

I don’t know what happened to the thieves except that I hope they choked on our rabbit ears. (“Shh…! The karma!”)

My father requested a transfer shortly after this day of riot, and our family moved to Ohio. Despite what Michigan fans say, this is not the same as drinking kerosene.

I am still not in charge.

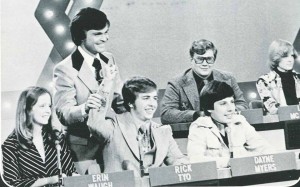

19 September 2015, Erin Waugh, “True Stories Told in the Key of E-flat”